Concept to Product in 6 Weeks: Baptism by Fire

When I look back at my product/object design schooling there is one project that stands out.

We had six weeks to design and fabricate an object that would be shown in one of the leading global design fairs, Salone de Mobile in Milan. This was early 2009, my second semester into gradschool. The project brief was roughly "design objects for an installation called Objects for the Age of Obama". So many potential pitfalls... something political at a design fair... naive and possibly stupid sounding (remember this was right after the election when Obamamania was sky high). Our professors knew that linking the show to a political theme, something Chicagoan yet global, would help attract mainly non-US Salone spectators.

I wanted to do lighting. Light is one of those powerful things that just attracts the eye. In a crowded fair? Design beautiful light that draws people in. Of course, execution is everything, and you have to be attuned to your senses. Lighting can literally be painful when done wrong. I knew this wouldn't be a problem, I know how to make beautiful things. I trusted my senses would guide me.

I focused on what I thought was most interesting about Obama, the way the rest of the World opened up to him. A kid with a Kenyan father who grew up in Hawaii, he was a cut from a more international cloth. For me this fostered hope for a more globally minded future.

I wanted this theme of interconnectedness to be captured in a singular image. I was thinking of ways to design maps and turn them into lighting fixtures. Then through researching, a NASA image of Earth from space (focusing on light pollution) struck me as the perfect way to address issues of power balance and interconnectivity. I found the image had depth. It literally shows who has power (power in it's many meanings, as electricity = political/economic power). It was also beautiful just on it's own. I knew I had to do something with this.

Getting these tiny pin-lights to shine through demanded an extensive exploration of materials and process. Fiberoptic wires were first considered, but this was ruled out due to complexity. I needed to perforate a material. At our design studio we had laser cutters, which are typically used for vector cutting (large single passes). I started (illegally) experimenting, I wanted to see if I could use a laser cutter as a punch-hole machine. The width of the laser is close to the size of a pinprick, time was running out and I had to experiment. Our school had many rules about what materials one can cut, and precise settings one can use. Lasers are dangerous. After many hours of failed attempts (and a couple late night fires) I found the solution. Finding the right material was part of the solution, using laminated archival paper provided enough material to not instantly cause a barn fire.

I turned the NASA image into a bitmap, inverted the colors (as our laser cutter was set to cut thecolor black). I then reversed the image, laser cutters create heat damage, and I knew that by reversing the material all heat damage would be facing in vs. out towards viewers.

I was able to essentially trick the laser cutter. It didn't know what it was cutting, and by manually adjusting power levels I was able to completely perforate the paper. I had figured out my fabrication method... the "laser pinhole machine" worked!

I choose a "perfect racetrack" lampshade form. It's flat sides and round corners enabled the most dynamic effect for the light. Finally, I used lampshade vinyl to evenly defuse the light across the form. As the show drew closer I wanted to find an elegant way to protect my process, this was achieved by obfuscating the object. I closed the form on both the top and bottom, creating a mystery box effect. The light quality was something people hadn't seen before, my mystery box effect was in full force. Everyone wanted to figure out what was going on.

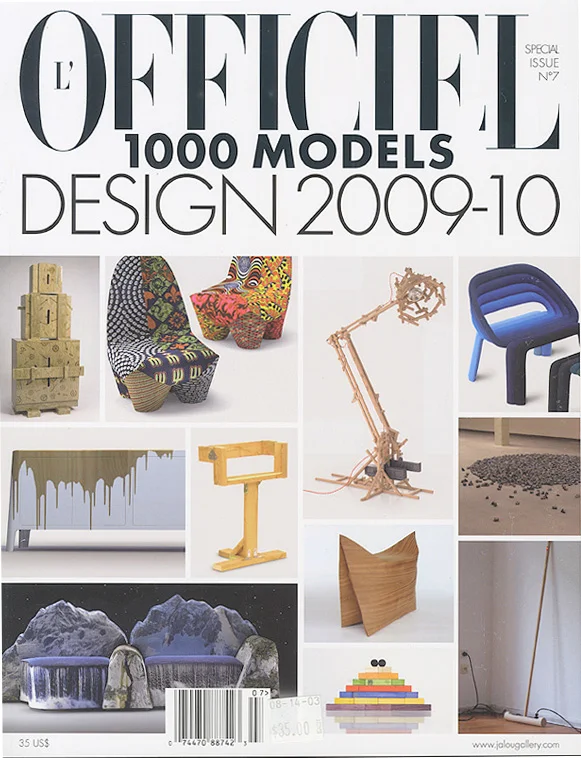

My lamp ended up being a star in the show, I was picked up by several publications and received a lot of inquiries during and after the show. It's hard to explain just how amazing this was... it was one the best times in my life. I enjoyed this process so much that I revised and expanded upon this fabrication technique for my graduating thesis.

I also ended up creating a new shade for a floor lamp later that year, and still to this day I have a version of this piece in my home. This project is still important to me. I believe it frames my process in the best light (pardon the pun). Every decision improved and enhanced the final object and experience.